Image Source: Unsplash

Mexico has found itself once more on the cusp of a generational opportunity to capitalize on newfound foreign investment to expand its industrial capacity. Recent economic history offers valuable insight into the challenges that the nation must overcome as it seeks to expand its participation in global trade.

By Nicolas Garza Perez Obregon

Edited by Shyam Dararajan

Mexico's economic history is characterized by a complex interplay between its economic and political spheres. Between 1976 and 1994, Mexico's recurrent economic crises coincided with the end of each presidential term, reflecting the country's struggle to balance its exchange rate management and its foreign debt policies. However, as NAFTA came into effect in January 1994, expectations arose for Mexico's economic growth. The revolutionary free trade agreement between Mexico, the United States and Canada heralded a reinvigorated trade era and outlined an optimistic trajectory for Mexico's increased participation in international trade. Like other major political reforms, the deal received stark criticism across borders yet heightened expectations for economic performance throughout the region. With recent increases in Foreign Direct Investment destined to expand industrial capacity, Mexico is once more courted by the promise of trade expansion by a collective of global investors. Such efforts are propelled by shifting ideals of international commerce that favor the localization of geographically vast supply chains.

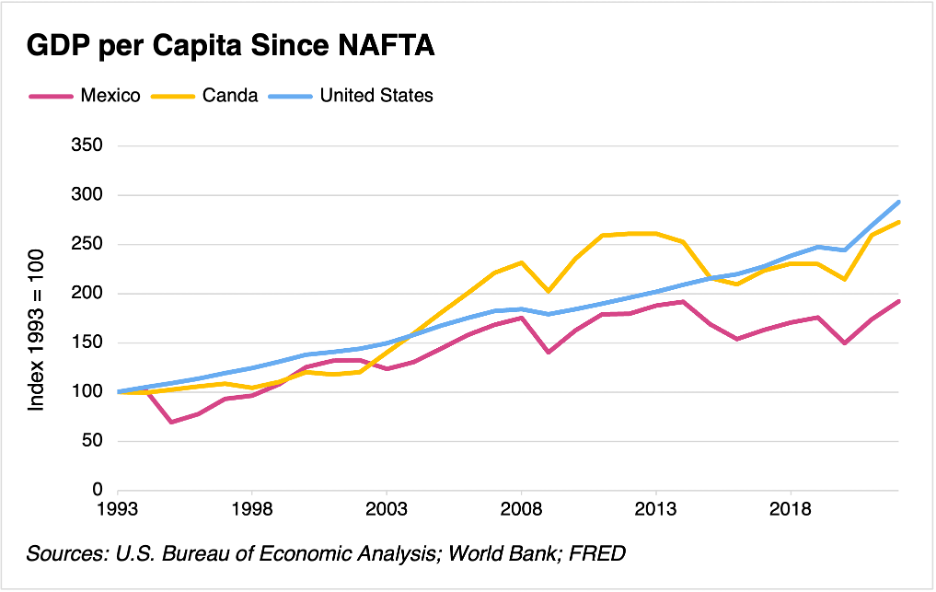

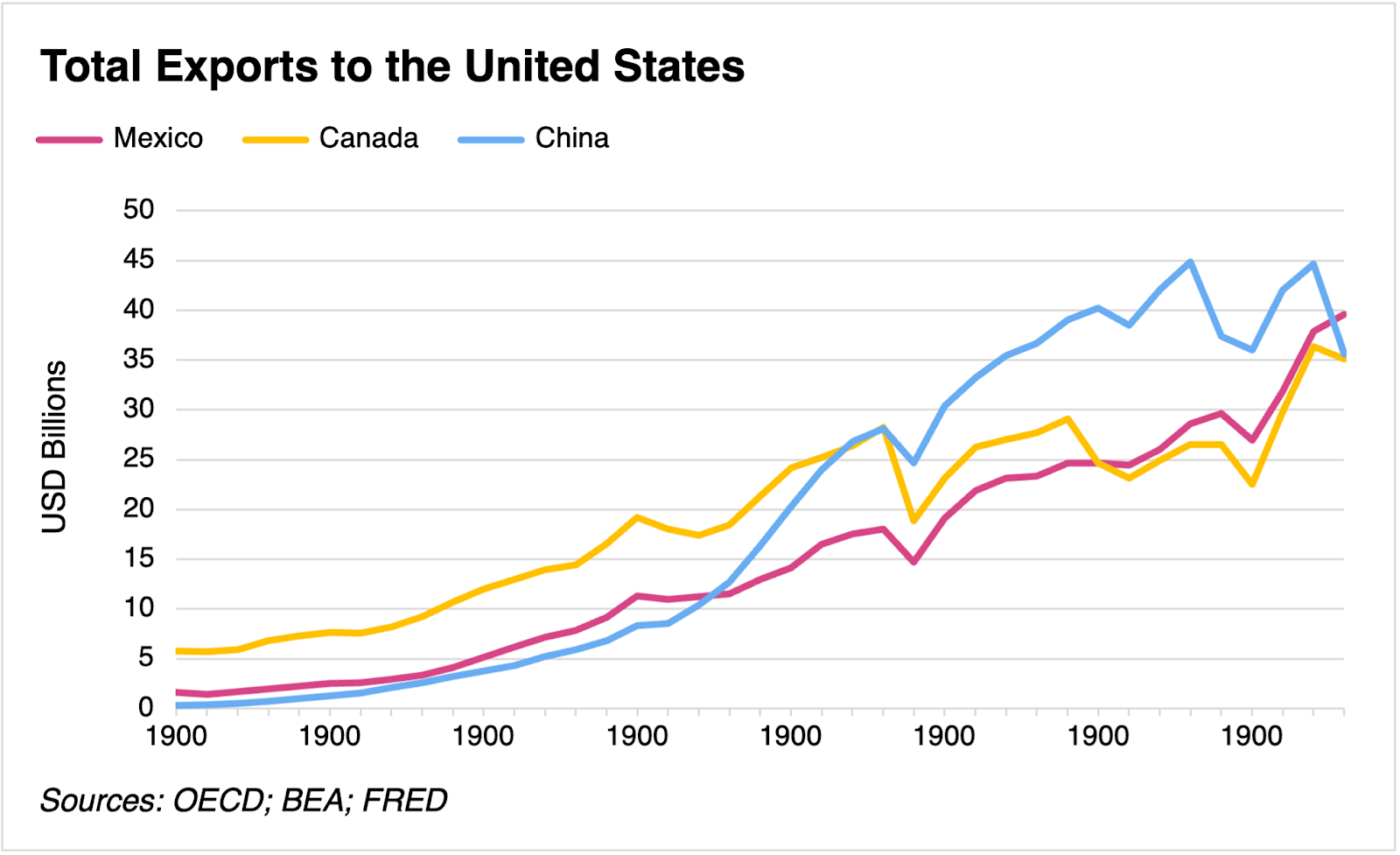

The promise of trade liberalization that swept from Eastern Europe through Latin America that delivered NAFTA in the early 1990s only partially materialized. Although the world has become more globalized since the deal's inception, there is no definite consensus on NAFTA's effectiveness. Trade increased significantly throughout the region after NAFTA's implementation, with American imports from Mexico growing ten fold from 1993 to 2019. Nevertheless, expectations for increases in Mexican GDP per capita were not met, totaling 26% between 1993 and 2019 and lagging significantly behind the US and Canada, which experienced a 48% and 44% rise respectively. Particular clauses that extended the tariff phase-out for some products up to 15 years after the deal's initial enforcement and the sheer complexity of the agreement drove divergent opinions concerning the treaty's success. Former President Donald Trump audaciously stated that "NAFTA is the worst trade deal maybe ever signed, anywhere" during a presidential debate in 2016. His comments expose the ambivalence with which NAFTA's policies were continuously met throughout its enforcement. After being elected, Trump and his administration proceeded to renegotiate critical terms of the original deal with the Peña-Nieto and Lopez Obrador administrations in Mexico and the Trudeau administration in Canada. Such diplomatic efforts culminated in the ratification of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement in March 2020. This amendment's effects on the signatories' economies find themselves, again, in constant dispute.

As the deal's provisions came into effect, Mexico struggled to grow its exports to the United States at a comparable pace to other nations like China. Although several theses attempt to explain the relative decrease in Mexico's exports to the US over the past few decades, the offshoring of manufacturing to other nations is widely regarded as the driving force behind this effect. Even though Mexico had a discernable geographical advantage, it found itself outcompeted by the operational efficiency that was achieved in overseas manufacturing centers.

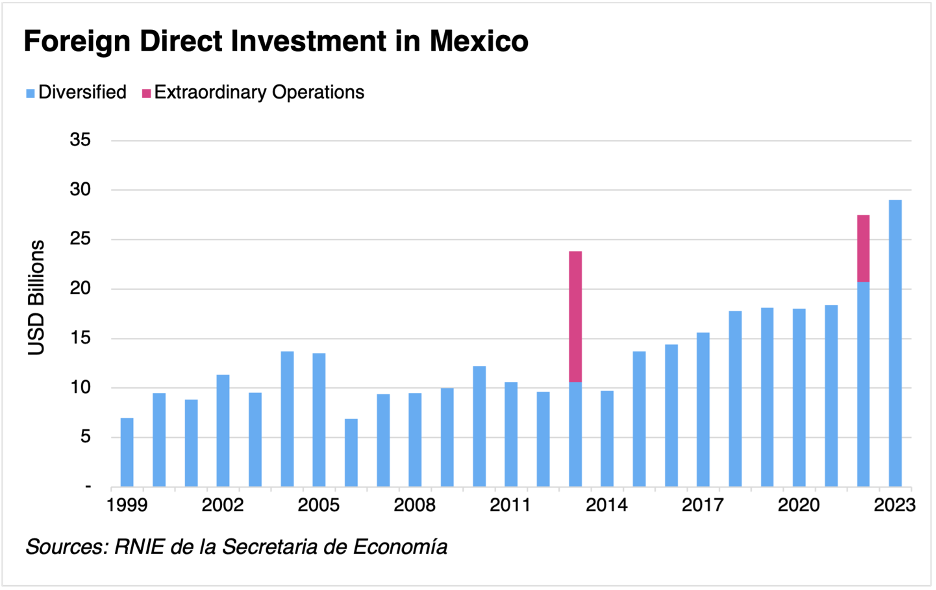

However, at the onset of the global COVID-19 pandemic, unforeseen social, political and economic shifts dramatically changed how people worked and consumed. The efficient yet fragile supply chains that globalization had delivered in previous decades revealed risks that were previously ignored in the optimism that enshrouded the offshoring movement. Additionally, increases in geopolitical risk across the globe in recent years exacerbated political support for initiatives that minimized supply chain risk. Hence, the southern neighbor of the world's largest economy renewed its presence as an attractive destination for foreign capital. The recent rally in Foreign Direct Investment experienced by Mexico exhibits investors' optimism in the region, particularly pertaining to the localization of industrial capacity.

This phenomenon, dubbed Near-Shoring, has received ample accommodation from Mexico's federal and state governments. Northern states with industrial economies, such as Nuevo León, were among those most suited to capture foreign investment. Federal initiatives, such as the Lopez-Obrador administration's recent fiscal incentive plan, attempt to broadcast the overarching message of economic attractiveness across borders and oceans. Nevertheless, these claims of profuse investment in the country risk becoming weaponized as Mexico prepares for its national election in June of 2024, which will decide key state governments and the presidency among a plethora of political positions. Investment achievement has been scarcely decoupled from their proponent's party's success, and a sudden sense of immediacy has crept into investment commitments that are uncertain or may reside in a distant timeline. Tesla's renowned commitment to building a Gigafactory near Monterrey, one of the nation's foremost industrial hubs, drew concern after Elon Musk's comments implied likely delays due to high levels of interest rates, refocusing the conversation across a global context of tightening financial conditions and the resulting uncertainty in the project's progression.

The evolution of the Near-Shoring phenomenon in recent years introduces a fascinating chapter of Mexico's economic history. This apparent reorganization of world trade dynamics deals a promising hand to the nation and revitalizes LSE economist Michael Reid's claim that "geography is economic destiny for Mexico." Nevertheless, the question of whether these economic shifts will deliver long-term benefits for Mexican citizens could also be framed as an inquiry into the degree of political readiness that exists in the country's institutions. As such will eventually be accountable for adequately administering the opportunity that has arrived from abroad. The absence of political and economic challenges within and beyond Mexico's borders is an unlikely scenario, and the opportunity awaits the leaders of organizations and institutions across Mexico to gain ground on their trek to a more prominent participation in the global economy.

No comments:

Post a Comment